Out of the Tar Pit

Abstract

Complexity is the single major difficulty in the successful development of large-scale software systems. Following Brooks we distinguish accidental from essential difficulty, but disagree with his premise that most complexity remaining in contemporary systems is essential. We identify common causes of complexity and discuss general approaches which can be taken to eliminate them where they are accidental in nature. To make things more concrete we then give an outline for a potential complexity-minimizing approach based on functional programming and Codd’s relational model of data.

Overview

-

In this author, the authors give recommendations for alternative ways of addressing the causes of complexity — with an emphasis on avoidance of the problems rather than coping with them.

-

There are two widely-used approaches to understanding systems (or components of systems):

- Testing

- Informal Reasoning

Our response to mistakes should be to look for ways that we can avoid making them, not to blame the nature of things

Causes of Complexity:

- Complexity caused by State: The reason that many of these errors exist is that the presence of state makes programs hard to understand. It makes them complex.

- Impact of State on Testing: The difficulty of course is that it’s not always possible to “get away with it” — if some sequence of events (inputs) can cause the system to “get into a bad state” (specifically an internal hidden state which was different from the one in which the test was performed) then things can and do go wrong. In fact the problem caused by state is typically worse — particularly when testing large chunks of a system — simply because even though the number of possible inputs may be very large, the number of possible states the system can be in is often even larger.

- Impact of State on Informal Reasoning: As the number of states — and hence the number of possible scenarios that must be considered — grows, the effectiveness of this mental approach buckles almost as quickly as testing (it does achieve some advantage through abstraction over sets of similar values which can be seen to be treated identically).

- One of the issues (that affects both testing and reasoning) is the exponential rate at which the number of possible states grows — for every single bit of state that we add we double the total number of possible states. Another issue — which is a particular problem for informal reasoning — is contamination. If the procedure in question (which is itself stateless) makes use of any other procedure which is stateful — even indirectly — then all bets are off, our procedure becomes contaminated and we can only understand it in the context of state

- As a result of all the above reasons it is our belief that the single biggest remaining cause of complexity in most contemporary large systems is state, and the more we can do to limit and manage state, the better.

- Complexity caused by Control: When a programmer is forced (through use of a language with implicit control flow) to specify the control, he or she is being forced to specify an aspect of how the system should work rather than simply what is desired. Effectively they are being forced to over-specify the problem. In addition, there is a second control-related problem, concurrency, which affects testing as well.

- Other causes of complexity: Finally there are other causes, for example: duplicated code, code which is never actually used (“dead code”), unnecessary abstraction3, missed abstraction, poor modularity, poor documentation.

- Complexity caused by Code Volume

- Complexity breeds complexity

- Simplicity is Hard

- Power corrupts: What we mean by this is that, in the absence of languageenforced guarantees (i.e. restrictions on the power of the language) mistakes (and abuses) will happen. The bottom line is that the more powerful a language (i.e. the more that is possible within the language), the harder it is to understand systems constructed in it.

Classical approaches to managing complexity:

- OOP: Conventional imperative and object-oriented programs suffer greatly from both state-derived and control-derived complexity.

- Functional Programming: The untyped lambda calculus is known to be equivalent in power to the standard stateful abstraction of computation — the Turing machine.

- In languages which do not support (or discourage) mutable state it is common to achieve somewhat similar effects by means of passing extra parameters to procedures (functions).

- It is worth noting in passing that — even though it would be no substitute for a guarantee of referential transparency — there is no reason why the functional style of programming cannot be adopted in stateful languages (i.e. imperative as well as impure functional ones)

- The trade-off is between complexity (with the ability to take a shortcut when making some specific types of change) and simplicity (with huge improvements in both testing and reasoning). As with the discipline of (static) typing, it is trading a one-off up-front cost for continuing future gains and safety (“one-off” because each piece of code is written once but is read, reasoned about and tested on a continuing basis).

- Logic Programming: Together with functional programming, logic programming is considered to be a declarative style of programming because the emphasis is on specifying what needs to be done rather than exactly how to do it.

- Pure logic programming is the approach of doing nothing more than making statements about the problem (and desired solutions). This is done by stating a set of axioms which describe the problem and the attributes required of something for it to be considered a solution.

Accidents and Essence

-

Essential Complexity is inherent in, and the essence of, the problem (as seen by the users).

-

Accidental Complexity is all the rest — complexity with which the development team would not have to deal in the ideal world (e.g. complexity arising from performance issues and from suboptimal language and infrastructure).

-

The obvious implication of the above is that there are large amounts of accidental state in typical systems. In fact, it is our belief that the vast majority of state (as encountered in typical contemporary systems) simply isn’t needed (in this ideal world).

-

We have seen two possible reasons why in practice — even with optimal language and infrastructure — we may require complexity which strictly is accidental. These reasons are:

- Performance

- Ease of Expression

-

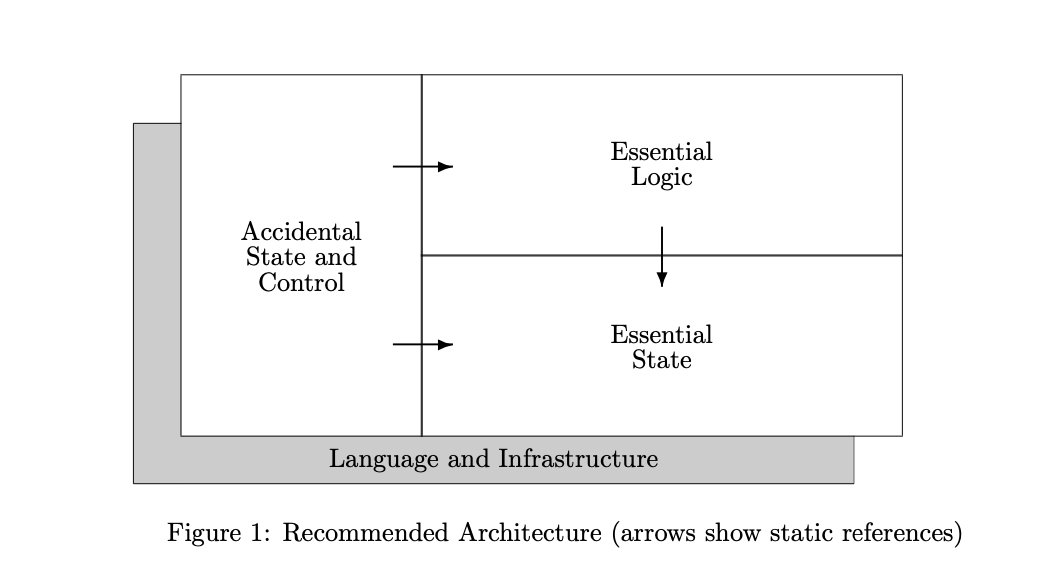

The key difference between what we are advocating and existing approaches (as embodied by the various styles of programming language) is a high level separation into three components — each specified in a different language. It is this separation which allows us to restrict the power of each individual component, and it is this use of restricted languages which is vital in making the overall system easier to comprehend. The only way to escape this risk is to place the goals of avoid and separate at the top of the design objectives for a system. It is not sufficient simply to pay heed to these two objectives — it is crucial that they be the overriding consideration. This is because complexity breeds complexity and one or two early “compromises” can spell complexity disaster in the long run.

The Relational Model

- The relational model has — despite its origins — nothing intrinsically to do with databases. Rather it is an elegant approach to structuring data, a means for manipulating such data, and a mechanism for maintaining integrity and consistency of state. These features are applicable to state and data in any context. A fourth strength of the relational model is its insistence on a clear separation between the logical and physical layers of the system.

- We see the relational model as having the following four aspects:

- Structure the use of relations as the means for representing all data

- Manipulation a means to specify derived data

- Integrity a means to specify certain inviolable restrictions on the data

- Data Independence a clear separation is enforced between the logical data and its physical representation.

Functional Relational Programming

- In FRP all essential state takes the form of relations, and the essential logic is expressed using relational algebra extended with (pure) userdefined18 functions.

- FRP recommends that the system be constructed from separate specifications for each of the following components:

- Essential State: A Relational definition of the stateful components of the system functions

- Essential Logic: Derived-relation definitions, integrity constraints and (pure)

- Accidental State and Control: A declarative specification of a set of performance optimizations for the system

- Other: A specification of the required interfaces to the outside world (user and system interfaces)

Conclusion

Complexity causes more problems in large software systems than anything else. Avoid it where possible, and to separate it where not. Specifically we have argued that a system can usefully be separated into three main parts: the essential state, the essential logic, and the accidental state and control.

Separation cannot be directly applied we believe the focus should be on avoiding state, avoiding explicit control where possible, and striving at all costs to get rid of code. So, what is the way out of the tar pit? What is the silver bullet?... it may not be FRP, but we believe there can be no doubt that it is simplicity.

Over the next few Saturdays, I'll be going through some of the foundational papers in Computer Science, and publishing my notes here. This is #20 in this series.