Hints for Computer System Design

Abstract

Studying the design and implementation of a number of computer has led to some general hints for system design. They are described here and illustrated by many examples, ranging from hardware such as the Alto and the Dorado to application programs such as Bravo and Star.

Introduction

-

There probably isn’t a ‘best’ way to build the system, or even any major part of it; much more important is to avoid choosing a terrible way, and to have clear division of responsibilities among the parts.

-

I have tried to avoid exhortations to modularity, methodologies for top-down, bottom-up, or iterative design, techniques for data abstraction, and other schemes that have already been widely disseminated. Sometimes I have pointed out pitfalls in the reckless application of popular methods for system design.

-

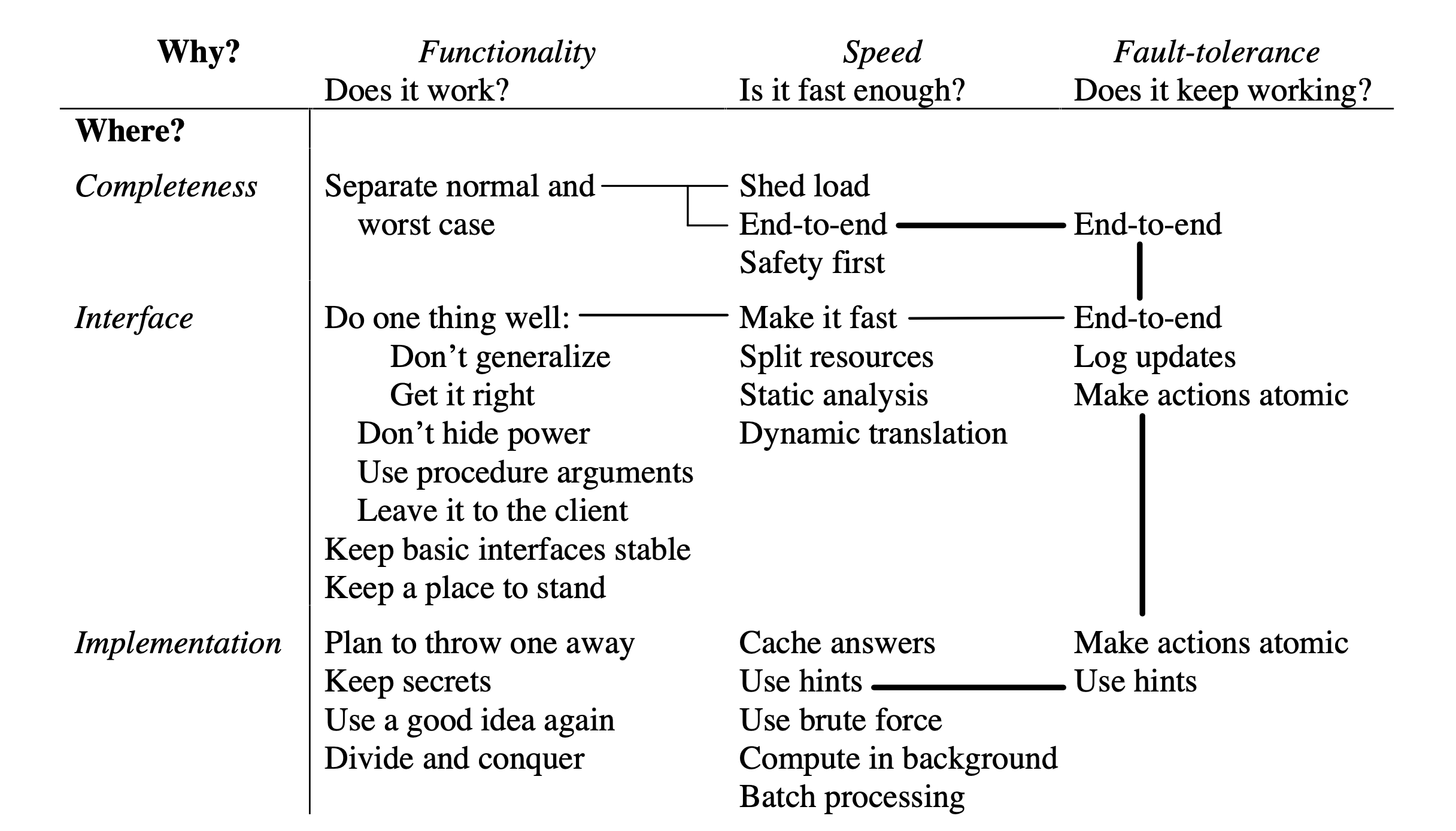

The figure below organizes the slogans along two axes: Why it helps in making a good system: with functionality (does it work?), speed (is it fast enough?), or fault-tolerance (does it keep working?). Where in the system design it helps: in ensuring completeness, in choosing interfaces, or in devising implementations.

Functionality

-

The interface between two programs consists of the set of assumptions that each programmer needs to make about the other program in order to demonstrate the correctness of his program. Usually it is also the most difficult, since the interface design must satisfy three conflicting requirements: an interface should be simple, it should be complete, and it should admit a sufficiently small and fast implementation.

-

The main reason interfaces are difficult to design is that each interface is a small programming language: it defines a set of objects and the operations that can be used to manipulate the objects.

-

Hoare’s hints on language design can be read as a supplement to this paper.

-

Keep it simple: Clients of the interface also depend on incurring a reasonable cost (in time or other scarce resources) for using the interface; the definition of ‘reasonable’ is usually not documented anywhere. If there are six levels of abstraction, and each costs 50% more than is ‘reasonable’, the service delivered at the top will miss by more than a factor of 10.

-

KISS: Keep It Simple, Stupid. If in doubt, leave if out.

-

Exterminate features: An interface should not promise features needed by only a few clients, unless the implementer knows how to provide them without penalizing others. A better implementer, or one who comes along ten years later when the problem is better understood, might be able to deliver, but unless the one you have can do so, it is wise to reduce your aspirations.

-

Get it right: Neither abstraction nor simplicity is a substitute for getting it right. Of course, this is not an argument against abstraction, but it is well to be aware of its dangers.

-

Make it fast, rather than general or powerful. The trouble with slow, powerful operations is that the client who doesn’t want the power pays more for the basic function. Usually it turns out that the powerful operation is not the right one. Machines like the 801 or the RISC with instructions that do these simple operations quickly can run programs faster (for the same amount of hardware) than machines like the VAX with more general and powerful instructions that take longer in the simple cases.

-

Don’t hide power: When a low level of abstraction allows something to be done quickly, higher levels should not bury this power inside something more general. The purpose of abstractions is to conceal undesirable properties; desirable ones should not be hidden.

-

Use procedure arguments to provide flexibility in an interface. The cleanest interface allows the client to pass a filter procedure that tests for the property, rather than defining a special language of patterns or whatever.

-

Leave it to the client: As long as it is cheap to pass control back and forth, an interface can combine simplicity, flexibility and high performance by solving only one problem and leaving the rest to the client. The success of monitors as a synchronization device is partly due to the fact that the locking and signaling mechanisms do very little, leaving all the real work to the client programs in the monitor procedures. The Unix system encourages the building of small programs that take one or more character streams as input, produce one or more streams as output, and do one operation

-

Continuity: Keep basic interfaces stable. When the system is programmed in a language without type-checking, it is nearly out of the question to change any public interface because there is no way of tracking down its clients and checking for elementary incompatibilities, such as disagreements on the number of arguments or confusion between pointers and integers.

-

When a system grows to more than 250K lines of code the amount of change becomes intolerable; even when there is no doubt about what has to be done, it takes too long to do it.

-

Traditionally only the interface defined by a programming language or operating system kernel is this stable.

-

Keep a place to stand if you do have to change interfaces. A rather different example is the world-swap debugger, which works by writing the real memory of the target system (the one being debugged) onto a secondary storage device and reading in the debugging system in its place

-

Making implementations work: Plan to throw one away; you will anyhow. It costs a lot less if you plan to have a prototype.

-

Keep secrets of the implementation: In other words, they are things that can change; the interface defines the things that cannot change (without simultaneous changes to both implementation and client). Obviously, it is easier to program and modify a system if its parts make fewer assumptions about each other

An efficient program is an exercise in logical brinkmanship.

-

One way to improve performance is to increase the number of assumptions that one part of a system makes about another; the additional assumptions often allow less work to be done, sometimes a lot less. Striking the right balance remains an art.

-

Divide and conquer

-

Use a good idea again instead of generalizing it: When the amount of data is large or the data must be recorded on separate machines, it is not easy to ensure that the copies are always the same. The transactional storage itself depends on the simple local replication scheme to store its log reliably. There is no circularity here, since only the idea is used twice, not the code. A third way to use replication in this context is to store the commit record on several machines

-

Handling all the cases: Handle normal and worst cases separately as a rule, because the requirements for the two are quite different: The normal case must be fast, the worst case must make some progress. The usual recovery is by crashing some processes, or even the entire system. At first this sounds terrible, but one crash a week is usually a cheap price to pay for 20% better performance.

Speed

-

Split resources in a fixed way if in doubt, rather than sharing them.

-

Input/output channels, floating-point coprocessors, and similar specialized computing devices are other applications of this principle. When extra hardware is expensive these services are provided by multiplexing a single processor, but when it is cheap, static allocation of computing power for various purposes is worthwhile.

-

Use static analysis if you can: Dynamic translation from a convenient (compact, easily modified or easily displayed) representation to one that can be quickly interpreted is an important variation on the old idea of compiling.

-

Cache answers to expensive computations, rather than doing them over. A serious problem is that when f is not functional (can give different results with the same arguments), we need a way to invalidate or update a cache entry if the value of f(x) changes

-

A cache that is too small to hold all the ‘active’ values will thrash, and if recomputing f is expensive performance will suffer badly. Thus it is wise to choose the cache size adaptively, making it bigger when the hit rate decreases and smaller when many entries go unused for a long time.

-

Use hints to speed up normal execution: A hint, like a cache entry, is the saved result of some computation. It is different in two ways: it may be wrong, and it is not necessarily reached by an associative lookup.

-

When in doubt, use brute force. Especially as the cost of hardware declines, a straightforward, easily analyzed solution that requires a lot of special-purpose computing cycles is better than a complex, poorly characterized one that may work well if certain assumptions are satisfied.

-

Compute in background when possible. In an interactive or real-time system, it is good to do as little work as possible before responding to a request. The reason is twofold: first, a rapid response is better for the users, and second, the load usually varies a great deal, so there is likely to be idle processor time later in which to do background work

-

Use batch processing if possible

-

Safety first. In allocating resources, strive to avoid disaster rather than to attain an optimum. Many years of experience with virtual memory, networks, disk allocation, database layout, and other resource allocation problems has made it clear that a general-purpose system cannot optimize the use of resources.

-

Bob Morris suggested that a shared interactive system should have a large red button on each terminal. The user pushes the button if he is dissatisfied with the service, and the system must either improve the service or throw the user off; it makes an equitable choice over a sufficiently long period. The idea is to keep people from wasting their time in front of terminals that are not delivering a useful amount of service. The original specification for the Arpanet [32] was that a packet accepted by the net is guaranteed to be delivered unless the recipient machine is down or a network node fails while it is holding the packet. This turned out to be a bad idea. This rule makes it very hard to avoid deadlock in the worst case, and attempts to obey it lead to many complications and inefficiencies even in the normal case. Furthermore, the client does not benefit, since it still has to deal with packets lost by host or network failure (see section 4 on end-to-end). Eventually the rule was abandoned.

-

The unavoidable price of reliability is simplicity.

Fault-tolerance

-

Making a system reliable is not really hard, if you know how to go about it. But retrofitting reliability to an existing design is very difficult.

-

End-to-end: Error recovery at the application level is absolutely necessary for a reliable system, and any other error detection or recovery is not logically necessary but is strictly for performance. Indeed, in the ring based system at Cambridge it is customary to copy an entire disk pack of 58 MBytes with only an end-to-end check; errors are so infrequent that the 20 minutes of work very seldom needs to be repeated

-

There are two problems with the end-to-end strategy. First, it requires a cheap test for success. Second, it can lead to working systems with severe performance defects that may not appear until the system becomes operational and is placed under heavy load.

-

Log updates to record the truth about the state of an object. A log is a very simple data structure that can be reliably written and read, and cheaply forced out onto disk or other stable storage that can survive a crash

-

Logs have been used for many years to ensure that information in a data base is not lost, but the idea is a very general one and can be used in ordinary file systems and in many other less obvious situations. When a log holds the truth, the current state of the object is very much like a hint (it isn’t exactly a hint because there is no cheap way to check its correctness).

-

To use the technique, record every update to an object as a log entry consisting of the name of the update procedure and its arguments. The procedure must be functional: when applied to the same arguments it must always have the same effect. In other words, there is no state outside the arguments that affects the operation of the procedure

-

The update procedure must be a true function: Its result does not depend on any state outside its arguments. It has no side effects, except on the object in whose log it appears.

-

Make actions atomic or restartable. An atomic action (often called a transaction) is one that either completes or has no effect.

-

Database systems have provided atomicity for some time, using a log to store the information needed to complete or cancel an action. The basic idea is to assign a unique identifier to each atomic action and use it to label all the log entries associated with that action. A commit record for the action tells whether it is in progress, committed (logically complete, even if some cleanup work remains to be done), or aborted (logically canceled, even if some cleanup remains); changes in the state of the commit record are also recorded as log entries. An action cannot be committed unless there are log entries for all of its updates. After a failure, recovery applies the log entries for each committed action and undoes the updates for each aborted action. Many variations on this scheme are possible

-

For this to work, a log entry usually needs to be restartable. This means that it can be partially executed any number of times before a complete execution, without changing the result; sometimes such an action is called ‘idempotent’

-

Atomic actions are not trivial to implement in general, although the preceding discussion tries to show that they are not nearly as hard as their public image suggests. Sometimes a weaker but cheaper method will do

-

Such occasional disagreements and delays are not very important to the usefulness of this particular system.

Over the next few Saturdays, I'll be going through some of the foundational papers in Computer Science, and publishing my notes here. This is #25 in this series.